The Sorry State of Honours & Awards in Canada

A Comprehensive Review of the State, Demand, and Potential of Recognition for the Canadian Armed Forces

Canada’s Honours and Awards System is nearly sixty years old. However, its history and roots stretch back to pre-confederation days, and it has seldom received the care and respect it deserves as an important Canadian institution. The system awards literal badges of honour to Canadians to recognize those who have excelled and inspire others to achieve their own greatness. The system is set up to be non-partisan and egalitarian yet faces political mismanagement and abuse by senior leaders. The system, as it is, favours senior leaders with access to honours seldom available to the rank and file, and issues within the system aren’t new or unique, which advocates argue is proof that military and government leadership are out of touch with Canadians.

Honours are an ancient form of recognition that endures with modern flair. Recognition is essential to people's self-worth; recognizing the hardest working and bravest of us encourages copycats to continue building and maintaining a society. When a person receives an Honour, not only does it reward their dedication and accomplishments, but they become leaders in their respective fields, encouraging others and setting a higher standard for those who follow. Failures to properly recognize people for their hard work usually disenfranchise those who would otherwise contribute significantly.

Advocates and veterans are sounding the alarm that the Honours system is out-of-date and out-of-touch. Stolen Valour continues to disparage the honour of veterans. Calls for creating new honours and awarding existing honours, supported by petitions and bills, ring in the halls of National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ) and Parliament.

This paper reviews a complex and niche issue in Canada. The first section briefly explains the Honours System's background, players, and nuances. The second section lays out the issues of the current state of the Honours System. The third section lays out the potential of the Honours System based on the advocacy demands from the military community.

BACKGROUND

Honours are a nation's official national awards, medals, decorations, orders, and titles. The Honours and Awards System, or simply the Honours System, administers the creation, criteria, awarding, revocation, and records of Honours and Awards. A nation’s Honours System is a key component of its national identity, similar to flags and coats of arms. Although most notable for the military, honours are very much part of the civil side, sometimes in other forms.

In Canada, Honours and Awards are administered by the Chancellery of Honours at the Office of the Secretary of the Governor General (OSGG) and, with delegated authority from the OSGG, by the Directorate of Honours and Recognition (DH&R) (previously it was the Directorate of History and Heritage (DHH)) at National Defence. However, ultimate control of Honours in Canada rests with the Sovereign, who is Fons Honoris, meaning “the Fount of all Honours,” and the Prime Minister, who has Ministerial Responsibility for Honours; Veterans Affairs has delegated authority from OSGG to issue and reissue older awards. The Honours Policy Committee advises them, which reviews and recommends policies and the creation of Honours. The mandate of the Honours Policy Committee is to ensure that the system is appropriately administered and isn’t undermined by the frivolous addition of unworthy or too numerous honours. The creation of new honours or the approval of foreign honours for wear are published in the Canada Gazette, the weekly official journal of the Canadian government announcing new or amended regulations, orders in council, statutes, and bills.

HONOURS HISTORY IN BRIEF

The history of Honours goes back to ancient Rome with the Corona Civica, the “Civic Crown” in Latin, which was awarded for saving the life of a fellow citizen. In Canada, Indigenous bands gave honours in the form of beads and the title of Band Chief. The British and French brought their Honours systems when the Colonial Europeans settled in North America.

The First World War saw Canadian women awarded honours for the first time, honoured for distinguished service and bravery, and 73 Canadians were awarded the Victoria Cross. When the Second World War dawned, the Canadian government allowed Canadians to receive British honours instead of creating Canadian honours. 16 Canadians were awarded the Victoria Cross, the last time the Victoria Cross would be awarded to a Canadian.

After the Korean War, veterans continued a tradition that has existed since the Fenian Raids, fighting for decades to receive recognition. Veterans of the Korean War had to fight until 1991 to receive the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal for Korea, after which the Canadian government started issuing medals more liberally.

In 1966, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson and former Governor General Vincent Masset determined that Canada needed its own honours system once and for all. On the 100th Anniversary of Confederation, the Government created the Order of Canada and, later that year, the Canadian Centennial Medal.

In 2008, in response to the war in Afghanistan that saw troops in combat unlike any mission since Korea, the Government created new medals to recognize that CAF members were unrecognized where they should be.

The tradition of commemorative medals in Canada was twice broken by Prime Minister Trudeau’s government, who refused strike medals recognizing Canada’s 150th anniversary in 2017 nor Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee in 2022, despite advocacy campaigns from Canadians. When the federal government refused to strike a Queens Platinum Jubilee, some provinces stepped up to fill the demand from community leaders and advocates.

“The brave and intelligent expect to leave to their posterity the splendour of their public services, embodied in rank and honour. A country that prohibits such a legacy destroys one of the chief sources of its greatness and blasts the vital principals of public virtue.”

Sir Arnold Wilson & Captain J.H.F. McEwan,

Gallantry: In Public Recognition and Reward in Peace and War

TYPES OF HONOURS

Honours and Awards are more than just medals; not all awards suspended by ribbon are medals. There is a misconception that all hanging awards are medals, Orders, Decorations, and Medals are all honours suspended by ribbon and worn on the left breast. Awards and Departmental Awards are national honours also worn on the left breast. Some Honours also confer post-nominals. There are National, Provincial, and non-official honours. National Honours are worn first, followed by Provincial and foreign honours.

Ribbons are pieces of cloth which suspend honours such as Orders, Decorations, and Medals, each with a unique arrangement of colours to differentiate the honour. Each ribbon is as different as possible, even when the medal itself is shared between honours, such as the United Nations Service Medals. Ribbons can also be worn by themselves for less formal military events or even for daily wear in uniform. Ribbons can also hold ribbon devices such as a bar, to show where and/or how many deployments they completed, numerals, maple leaf’s, or rosettes to denote subsequent awards.

Not all honours are awarded to individuals; some can be awarded to multiple people for the same act, and there are also Unit Awards. Unit Awards are honours bestowed upon an entire military unit: Commendations and Battle Honours. Unit Commendations have pins that can be worn with a person’s honours; Battle Honours are carried on a unit’s Colours. Every standing military unit has Colours, flags used to signify a unit’s position on the battlefield and carry the Battle Honours of that unit. Battle Honours have been awarded to Canadian units for Afghanistan, World War One and Two, and as far back as the War of 1812.

Titles, such as Baron, Duke, or Knight, are also National Honours; however, Canada does not award titles. On occasion, Canada will permit its citizens to accept titles from foreign governments.

ORDERS

Orders are societies of highly skilled and dedicated people invested for long and meritorious service in their respective fields. Canada has three national Orders: the Order of Canada, the Order of Military Merit, and the Order of Merit for the Police Forces. Each order welcomes the very best after a lifetime of service, one of the three levels: Member, Officer, and Commander. Each of the provinces and territories have their own Orders. With government permission, Canadians may also be invested in certain foreign and commonwealth Orders, such as the Royal Victorian Order and the Order of St. John.

The Order of Canada is Canada’s matriarch of Honours, the original honour created for Canadians by Canada and administered in Canada.

DECORATIONS

Decorations are awarded for acts of extreme devotion and accomplishment. Meritorious acts are awarded the Meritorious Service Cross or the Meritorious Service Medal in either the Military or Civil category for work benefiting Canada or their community. Acts of Bravery are awarded either the Medal of Bravery, the Star of Courage, or the Cross of Valor for risking their life to save others. Acts of gallantry on the battlefield are awarded the Medal of Military Valor, the Star of Military Valor, and the Victoria Cross for decisive actions in battle.

The Victoria Cross is Canada’s highest Honour. It succeeded the British Victoria Cross, which was available to Canadians until the creation of the Canadian Honours System.

MEDALS

Medals are awarded for service to the nation and are not limited to military service. Service medals are awarded for service on a military operation; civilian police officers and civilian staff can also be awarded service medals. Service medals are awarded by Canada, the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and occasionally by allied nations.

Commemorative medals are awarded for faithful or meritorious service on special occasions such as the anniversaries of Confederation and the Coronation and Jubilees of Monarchs. Commemorative medals are one of the oldest forms of public recognition still in use, and its tradition in Canada goes back to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are given an allotment of commemorative medals and other federal, provincial, and municipal uniformed services; however, more than 2/3 are awarded to civilians through elected officials at each level of government.

Long Service or Exemplary Service Medals are awarded for long and honourable service in a uniformed service. Other medals are awarded as well: the Sacrifice Medal for wounds resulting from enemy action, the Sovereigns Medal for Volunteer Service (formerly the Caring Canadian Award), the King's Medal for Champion Shot for winning the annual Canadian Forces Small Arms Competition, and more. Non-government organizations also have their own medals; some are approved for wear, such as the St. John Ambulance Service Medal and the Commissionaires Long Service Medal.

AWARDS

Awards are awarded for distinguished service and recognition. Commendations are awarded with a pin for wearing with national honours, as is the Memorial Cross, while the Mention in Dispatches is worn on the ribbon for the deployment (otherwise can be worn with the commendation pins). Most awards are for service above and beyond the call of duty; however, not all are. The Memorial Cross is awarded to the next of kin of fallen CAF members, and the Canada Pride Citation was issued to recognize historical injustices towards LGTBQ+ CAF members who were bullied out.

In addition, while not formally part of the Honours System, Departmental Awards are worn with official honours. Departmental Awards are issued by the Department of National Defence itself for commendation or qualification.

FOREIGN HONOURS & AWARDS

Commonwealth and foreign nations are occasionally awarded for acts committed while deployed with or employed by other nations. Not all are approved for wear; those that are will be published in the Canada Gazette.

NON-OFFICIAL HONOURS

While the government controls national or official honours, any organization may use medals as part of its recognition system. Non-official medals or honours may not be worn on the left breast; however, they are permitted to be worn on the right breast. Organizations such as the Canadian Cadet Movement and the Royal Canadian Legion have their own honours systems, commonly mistaken for national honours; most Canadians don’t know the difference between honours worn on the left side versus the right side.

For a more complete understanding of Honours and Awards in Canada, consider reading “The Beginners Guide to Canadian Honours” and “The Canadian Honours System” by Dr. Christopher McCreery

HONOURS & AWARDS PLACE IN MILITARY CULTURE

The military is indeed a culture of its own. It has its own institutions, history, identity, customs, heroes, courtesies, music, ceremonies, dialect, art, rituals, and values. It is a culture shared around the world and across history, and it has its own symbolism. Honours are an element of military culture’s symbolism. Each award symbolizes the individual’s achievements, akin to how a member of another culture may display an icon or accoutrement that signifies an achievement or status. Others recognize these symbols outside the culture for their significance, even without understanding their meaning.

“A soldier will fight long and hard for a bit of coloured ribbon.”

Napoleon Bonaparte

In military culture, in formal settings, one wears honours on one's uniform to proudly show one's achievements without rudely bragging and without judgment or envy from others. In Canada, it is also customary for veterans to wear their awards in formal settings within military settings. Each medal or specialist badge shows others from their culture their career accomplishments. To others, they can read the awards and know which deployments they served on if they stood out and received a medal or commendation for meritorious service or proved their worth through gallantry. A proud display of accomplishments is seen as an inspiration to others to achieve their own greatness. Every personal achievement is an achievement for the whole organization. Each person who is awarded an honour demonstrates the worth of the Canadian Armed Forces and Canada. As such, honours and awards are a central tenet of the esprit de corps of the military culture and community.

One of the military’s influences on our society is honours. Canada’s premiere honour, the Order of Canada, as well as bravery medals, the civil division of the Meritorious Service medals, and commemorative medals are routinely awarded to Canadian civilians. Civilian contributions to Canada should indeed be recognized, and medals have become a popular way of recognizing those who have made a notable impact on their country or community. Civilian honourees proudly wear their full-size or mini-medals at formal events.

ISSUES

No system is perfect, and the Honours System is no exception. Advocates, serving members, and veterans have brought forward complaints and shortcomings about a system that is complex and misunderstood by most, including veterans. The issues presented represent the challenges for the Honours System and a few roadblocks between the CAF and solving its retention crisis.

TOXIC MILITARY LEADERSHIP

Toxic leadership is not a new concept for militaries, and its effects are far-reaching. When discussing toxic leadership in the CAF, advocates rightfully highlight and focus on abuse, harassment, gender and racial integration, and systemic abuses. However, the concentration of recognition is a needed part of the discussion.

Nepotism is a frequent and troublesome problem plaguing junior officers and non-commissioned members who do not benefit from its privileges. Nepotism is not the same as what is colloquially referred to as “rank has its privileges (RHIP)” amongst military members. RHIP reflects that the workload shifts from physical work in a field environment to administrative and less-austere tasks as rank levels increase. RHIP means that there are incentives for members and officers who persevere and advance in rank. Nepotism is when senior leaders gatekeep benefits, awards, or privileges, not to mention postings, deployments, or promotions, for themselves and their friends.

The senior leadership of the Canadian Armed Forces has been the spectacle of national news media countless times over the lifetimes of current serving members, from sexual assault scandals to affairs to corruption to even more sexual assault scandals. In the 1998 article Canada's fighting poor are fighting mad, O’Hara et al. describe the Minister of National Defence and Chief of Defence Staff continuing 5% bonuses for Colonels and up while the troops were losing pay, even with Minister Eggleton stating, “I find the conditions our military are living under unacceptable.” In her book The Ones We Let Down: Toxic Leadership Culture and Gender Integration in the Canadian Armed Forces, Duval-Lantoine describes how the CAF leadership dragged their feet on gender integration and caused significant trauma for members. In his 2024 article Soldiers leaving Canadian Forces over 'toxic leadership,' top advisor warns, Pugliese describes soldiers leaving the CAF because of toxic leadership.

“Toxic leaders, more often than not, appear trustworthy and effective. Organizations, in spite of themselves, can enable toxic leaders, or amplify their impact. Because organizations focus on result more than processes, if the leader’s actions appear to further institutional goals, the organization accommodates destructive personalities and tolerates negative behaviours.”

Charlotte Duval-Lantoine,

The Ones We Let Down: Toxic Leadership Culture and Gender Integration in the Canadian Armed Forces

Serving members often lament the Chain of Command for doing very little for Honours & Awards. To nominate a member for an award, forms and supporting statements must be prepared, citations and arguments must be presented to the higher levels in the Chain of Command and finally approved at NDHQ. Each application has significant challenges at each level, even for bravery or gallantry decorations, often leading to outright rejection or supplemented for an untracked paper commendation or coin. These challenges lead to many leaders giving up before getting started.

“Maintenance of morale. After leadership, morale is the most important element in ensuring cohesion and the will to win. Morale is, however, sensitive to material conditions and should never be taken for granted. It is nurtured through good leadership, sound discipline, realistic training, confidence in equipment, and a sense of purpose.”

Principles of War, CFJP 01: Canadian Military Doctrine

The process is significantly easier, however, for those in higher headquarters. In higher headquarters, such as formation and higher, nepotism plays a significant factor as the approving authorities and nominees are, at the least, co-workers. Officers have been known to brag about writing each other up for Merit Decorations while their staff of junior officers and non-commissioned members get nothing. Senior officers at NDHQ, who make two to four times the base salary as the troops, are pushing back against new decorations, calling advocates “badge collectors” and “trophy seekers.” Advocates argue that those very same senior leaders, adorned in various Merit Decorations and Foreign Decorations, are the “badge collectors.”

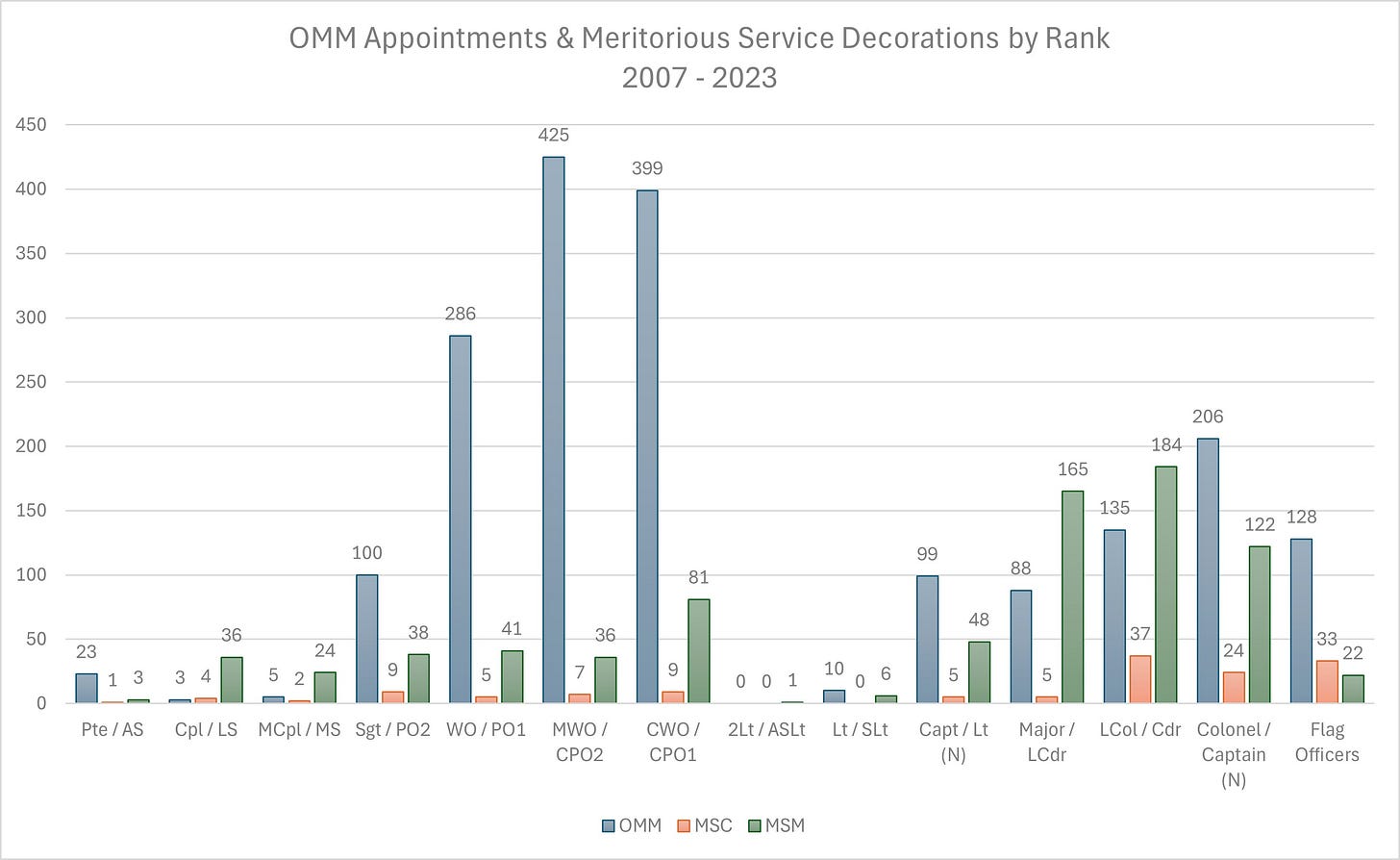

A review of DH&R’s annual publications for Honours & Recognition for members of the CAF from 2007 to 2023 shows that Chief Warrant Officers, Chief Petty Officers, and Master Warrant Officers receive a significantly larger share of appointments to the Order of Military Merit, while senior officers receive a larger share of Meritorious Service Decorations. This review only considered awards to members of the CAF and did not count awards to civilians or foreign officers; Rangers were counted as Privates.

A review of Surgeon Captain John Blatherwick’s report Foreign Military Awards to Canadians shows that the senior officers of the CAF are indeed receiving the lion’s share of foreign decorations. By far, the largest supplier of foreign decorations was the United States; France appointed many World War Two veterans as Knights in the Legion of Honour. This report also tracked decorations awarded to members of the RCMP, civilians, and a Governor General.

This is not to argue that those who received the above decorations or appointments were undeserving; it is, however, hard to dismiss the differences in recognition between senior non-commissioned members and senior officers versus junior non-commissioned members and junior officers. It is also worth noting that their staff enabled many accomplishments that earned the above decorations or appointments.

STOLEN VALOR

Stolen Valor is the act of impersonating a serving military member or veteran by use of uniforms, honours, documents, and/or false claims of service in order to gain unearned admiration or benefits from others. It is a sad and persistent issue impacting the military community. The act of stolen valour is implemented by those who seek to bathe themselves in the honour and achievements of military members without engaging in the heroic or difficult tasks that military members engage in. Civilians and military members alike undertake acts of stolen valour, some suffering notable mental health issues, others seeking unearned recognition to boost their self-worth or even veteran benefits. Stolen valour is not the same as simply wearing camouflage or pieces of a military uniform, nor is cosplay or Live Action Role-Playing (LARP-ing), nor is wearing or displaying the honours of a family member (it is not allowed for anyone, even families, to wear the medals or awards of someone else, however, it is not stolen valour); stolen valour is only when there is an attempt to deceive for personal benefit.

To military members and veterans, the honours worn are representative of the uniquely difficult career and assignments that make the military stand out from other institutions. Each one, especially honours conferred for acts of gallantry, is indicative of the heroic and noble acts that enshrine the legacy of the military and those who serve. Each act of stolen valour carries ramifications to the entire military community, as those who have not earned an honour tarnish the reputation of those who have. Embellishers are incapable of providing faithful witness to the acts they are claiming and, as such, are damaging to the credibility of those who have. Claims to have endured hardships or accomplished incredible feats represented by wearing an honour is an insult to those who have.

In Canada and other nations, stolen valour is a crime. Despite this, Canadians continue to disregard the law to embellish or completely fabricate their honours. While some attempts at stolen valor are laughable, others show some sophistication in the research and effort to fabricate a presentation and narrative demonstrating a conscience effort to deceive; it should go without saying that those who must fake honour have none. Noted American writer Ernest Hemingway thoroughly expressed this sentiment in his 1920 article in the Toronto Star Weekly, in which he mockingly instructs embellishers in the art of stolen valour.

“Now you have service at the front, proven patriotism and a commission firmly established, there is only one thing left to do. Go to your room alone some night. Take your bankbook out of your desk and read it through. Put it back in your desk. Stand in front of your mirror and look yourself in the eye and remember that there are fifty-six thousand Canadians dead in France and Flanders. Then turn out the light and go to bed.”

Ernest Hemingway, Popular in Peace – Slacker in War, Toronto Star Weekly, 13 Mar 1920

Moreover, because perpetrators of stolen valour are not merely seeking gratification, often seeking donations, discounts, or benefits which are provided to veterans, there is an element of fraud. Some veterans argue that the act of stolen valour itself is defrauding the military and those who serve. What is certain is that those fakers who seek a veteran's benefits are defrauding those who may be convinced. Some fakers have even managed to fool politicians and community leaders to get themselves awarded real honours such as commemorative medals or commendations. Most are rewarded for their fakery with invitations to lavish events and places of honour. Some use their fakery to obtain or advance careers at organizations which seek veterans for their skills and leadership. Unfortunately, there is no measure in the legislation to separate those who have committed stolen valour for self-gratification from those who have to defraud others.

Section 419 of the Criminal Code of Canada forbids the act of stolen valour, yet it does little to discourage acts of stolen valour. The legislation was implemented in 1985, and after its 2018 amendment, it is largely unchanged from its original version; it doesn’t even define stolen valour by military members. Some in the military and veteran communities are calling for stiffer penalties, and the lack of proactive enforcement has led to the creation of Stolen Valor Canada, a volunteer veteran-led watchdog group monitoring, evaluating, and reporting cases to local police services to address the issue. The penalty for stolen valour is low, a summary conviction, although with the number of cases that stem from a mental health issue combined with the fact that stolen valour is a non-violent crime, “throwing the book at them” would not serve the public good nor heal the damaged reputation of the military community. However, an amendment to the legislation to ensure that a mental health evaluation is conducted would not only help the accused find the self-worth they seek within themselves, but it should prevent recidivism if they can access therapy. As would enforcing a mandatory community service sentence to an incorporated veteran-service organization, which should impart an increased level of understanding and respect for the service and sacrifices of the military onto those convicted; forbidding anyone from marketing or selling a medal that may be confused with an official honour; requiring sellers of medals, particularly custom and non-official awards, to state that only official honours may be worn on the left breast and only by the recipient; and, adding additional wording for presiding justices to levy stricter sentences only for those who have defrauded others.

Part of the problem is that most Canadians know so little about the CAF that the ability to detect a fake honour or a fake veteran is beyond most. While it is foolish to expect that a civilian would be able to sniff out a well-prepared faker, it would not, however, be foolish to expect politicians or organizations, including the media, to know how to verify someone’s claims before an interview, ceremony, award, or invitation. The proactive approach by politicians and organizations to verify a veteran's claims is not undertaken consistently or thoroughly, which results in the same politicians and organizations propping up fakers. A notable offence in recent Canadian history took place in the House of Commons in September 2023 when Speaker Anthony Rota invited a living nazi who fought against the Allies for the Ukrainian SS Division to a special ceremony with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Although the invitee was not engaged in stolen valour, the incident demonstrates that not even in the highest ranks of Parliament do politicians or their staff know enough about the military even to know how to verify someone’s service, whom to ask for help, or that they should seek professional guidance. Not only was the incident a blow to the credibility of Speaker Rota, leading to his resignation, and a blow to the credibility of the Government of Canada on the international stage, but it was also a slap in the face to Canada’s veteran community; which includes not only Ukrainian-Canadians but also veterans who have served in the Ukrainian International Legion in their fight against the Russian Invasion who have returned to Canada.

Another issue making it easy for fakers to sneak past authorities is that the searchable database of Canadian Honours is limited. The Order of Military Merit, Meritorious Medals, Valor, Bravery, and Mention in Dispatches are the only military honours available in the searchable database on the Governor General's website; commemorative medals and Governor General's awards are also included. The database does not include service in the military, service medals, the Canadian Forces Decoration, specialist badges (such as parachute wings or the sea service badge), or commendations. During their legislative work to criminalize stolen valour in the US, a public, searchable database including all honours, including departmental awards, was a key recommendation to advancing the issue. Expanding the Canadian database will adversely impact the ability of fakers to deceive.

Of note: the US attempts at Stolen Valor legislation are struggling because the 1st Amendment to the US Constitution, Freedom of Speech, has explicitly been deemed to protect lies and deception below the fraud threshold. Which, to say the least, is offensive to many US veterans and service personnel.

“The simple act of lying--even about receipt of a military decoration--is, by itself, protected speech.”

House Report 113-84 - STOLEN VALOR ACT OF 2013, House Judiciary Committee, United States Congress

Another method to combat fakers could be the veteran’s identification card. NDI 75, the ID card issued to Canadians released from the CAF, is a plain and simple card that does little to detail a veteran's service. South of the border, veterans who have separated from the US military are issued their DD-214. A DD-214 lists the veteran’s deployments and honours along with their rank, element of service, enrollment and release dates, and trade. Modernizing the NDI 75 to carry more service data would enable civilians to verify a veteran’s status in a less formal or administrative capacity.

COMPLAINTS FROM SERVING AND VETERANS

Members and officers alike have expressed that Canada’s Honours and Awards System is outdated, favouring senior officers over junior officers and non-commissioned members, and lacking modern recognition. Canadians serving with our allies have learned there are better options than the limited Commonwealth systems provide. However, as serving military members are forbidden from any forms of organized advocacy or collective bargaining, much of the advocacy work falls on veterans.

Veteran-led advocacy campaigns have taken many forms in Canada, from letter and phone campaigns to meetings with parliamentarians to e-petitions to Facebook groups. Veterans have been calling for the government to issue new medals, which have been largely disregarded for decades, to address long-standing inequalities. The fact that NDHQ is a loud voice of opposition is especially aggravating for these advocates. NDHQ and DHH insist that the system is adequate; however, advocates assert that senior officers at NDHQ are quite liberal when awarding the Order of Military Merit and Meritorious Service Decorations to each other and exchanging foreign medals with attachés. Advocates argue that the current system favours senior officers for completing postings, while junior officers and non-commissioned members who outperform or accomplish feats are denied formal recognition. They argue that senior leadership at NDHQ is not interested in changing a system that disproportionally benefits senior leadership. Therefore, their demand is for the government to step in.

THE EFFECTS OF LACKING RECOGNITION

Lacking recognition is not just a military phenomenon; it is also persistent in the corporate world. As such, human resources researchers have research that supports arguments in favor of recognition. Recognition is not just about showing off your awards; it’s about feeling a sense of worth and value for the labour and accomplishments an employee has provided their organization.

In their paper “An analysis of the utilization and effectiveness of non-financial incentives in small business”, Appelbaum and Kamal argue that in addition to pay equity, employees had greater job satisfaction when provided a challenging work environment, job evolution, and recognition. Recognition in an organizational context is critical to ensuring that the behaviours desired by the organization are repeated. Contributing to an employee’s job satisfaction benefits the organization’s performance and productivity. They argue that failure to recognize employees leads to low levels of engagement, early departures, and even sabotage. Unfortunately, some managers see recognition as a costly and unnecessary use of resources.

“…there is a vast amount of evidence suggesting that validation of task accomplishment by peers is a strong predictor of employee satisfaction.”

Steven Appelbaum, Concordia University, and Rammie Kamal, Dover Finishing Products, Inc.

An Analysis of the Utilization and Effectiveness of Non-Financial Incentives in Small Business

In their paper “An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices”, Brun and Dugas argue that there are ethical considerations for employee recognition, especially equality amongst people and dignity. Leadership works best when they stand up for their employees. They further argue that in addition to ethical considerations are humanistic considerations demonstrating that employees are people with needs and agency. Employees perform better when able to voice their concerns and influence the organization. Recognition of work practices is often more beneficial than work accomplishments, as the dedication and expertise demonstrated is the factor to reward. They argue that behaviorally, organizations ought to recognize the behaviours they deem worthwhile.

“This sense of being appreciated by one’s peers makes employees feel that they belong to a community.”

Jean-Pierre Brun, Université Laval and Ninon Dugas

An Analysis of Employee Recognition: Perspectives on Human Resources Practices

The evolution of employee recognition is part of the overall progressive trend of employee empowerment from ancient systems of slave workforces toward humanistic work practices. Recognition is evolving as employees find empowerment and are able to voice their concerns and demands in a holistic environment and in cooperation with their management.

DEMANDS FROM THE COMMUNITY

Moving forward will require the Government to take a more active role in the administration of Honours if it wishes to honour the service of CAF members and keep its promises to recognize the difficult and tremendous job the CAF accomplishes. The following are potential options for the Government and DND to consider in order to address the demands of the military community and the shortfalls of the current Honours System.

THE VICTORIA CROSS

The Victoria Cross is Canada’s highest Honour, awarded for the most conspicuous acts of gallantry in extreme peril. The British Victoria Cross was awarded to Canadians for heroics in the Boer War, World War One, and World War Two, but it ended when Canada instituted its own Honours System in 1967. In 1993, the Government created the Canadian Victoria Cross; however, it has never been issued. The veteran-led advocacy group Valor in the Presence of the Enemy seeks to change that. In contrast, since 2001, the US has awarded 28 Medals of Honor, Australia has awarded three Australian Victoria Crosses, and the UK has awarded three Victoria Crosses.

The story of Jess Larochelle has become a legend in the Canadian military community. On the 26th of October 2006, Private Larochelle’s unit was attacked by insurgents. His position was struck by an RPG, knocking him unconscious and leaving him with a broken back. He regained consciousness to discover two of his teammates had been killed and four others wounded. He climbed back to the C6 machine gun to defend against the continuing attack. The turret of the LAV III on that side malfunctioned, leaving the lone private to sustain fire, keeping the insurgents at bay. Larochelle continued firing M72 rockets, which exacerbated his pain, when the C6 was destroyed by incoming fire. The following day, Larochelle continued his duty to his fallen comrades by performing in the Ramp Ceremony before being repatriated. Larochelle was awarded the Star of Military Valor.

Advocates and veterans are demanding that the government award him the Victoria Cross instead and review other cases of underrecognition. NDHQ insists it has made the right decision. E-petition e-3636 was put forth by advocates who are tired of a system that rewards administrative work more than gallantry. Jess Larochelle died in 2023; however, that has not stopped advocates and veterans from their advocacy.

DOMESTIC OPERATIONS MEDAL

The proposed medal would recognize CAF, RCMP, and first responders for service during a Domestic Operation within Canada.

Domestic Operations are operations within Canada, including the defence of Canada, search and rescue, naval operations against illegal trafficking or fishing, support operations to remote installations, avalanche prevention, ceremonial duties, and aid to civil power. For this medal, only operations responding to a national emergency, such as out-of-control fires, flooding, natural disasters, responding to a pandemic, plane crashes, and aid-to-civil power. The intent is to recognize service above and beyond the typical military service while responding to an emergency.

Canadian Armed Forces personnel often participate in domestic operations in partnership with other federal, provincial, and municipal services in times of national emergency. The CAF is particularly in demand when the scope exceeds the capabilities of first responders and other government departments. The CAF is regarded as a measure of last resort; however, Provincial governments make numerous requests each year for the CAF’s ability to provide hundreds of trained and organized personnel and unique heavy equipment.

Campaigns to strike a medal recognizing domestic operations service have been ongoing for decades. Veterans argue that domestic operations are no less deployed operations than OUTCAN operations. A domestic operation, albeit shorter and within Canada, carries risks and hardships like any operation. The operations are a national priority and bring immediate benefits to the affected communities. Sadly, one notable difference between a domestic natural disaster response and a foreign natural disaster is that when deployed domestically, it is suffering Canadians that troops are witnessing and assisting members of their own communities in some cases. Soldiers are also exposed to risk, from fighting fires to sicknesses from flooding to exposure during pandemic responses, and risks outside their formal training and profession.

NDHQ has pushed back against recognizing domestic service. Their position is that all service in Canada is recognized with the Canadian Forces Decoration. However, that isn’t the case. The Special Service Medal is awarded with a bar for both ALERT, for deployment to Alert, Nunavut, and DISTANTIA, for UAV support of deployed operations from Canada. Arguably, the UN Headquarters Medal, which is awarded for postings to the UN Headquarters in New York, could also be considered domestic service. There are also medals for which members can qualify if they support an OUTCAN operation(s) from Canada or the US.

Grassroots campaigns for the creation of the medal have taken the form of e-petitions, e-1884 and e-4321, and have led to private member bills in the House of Commons, C-514 (37th Parliament), Bill C-386 (39th Parliament) and C-231 (44th Parliament), and a recommendation from the Parliamentary Committee for National Defence. Politically, the government seems to understand the demand from the military community and its benefits, as Prime Minister Trudeau erroneously gave direction to the Minister of Veterans Affairs in his 2021 Mandate Letter to recognize domestic operations, a direction which should have been given to the Minister of National Defence. Advocates for the medal further argue that Australia’s National Emergency Medal is a prime example of what could be.

“Ensure that modern Veterans, as well as women, Indigenous, racialized and LGBT2Q Veterans from all conflicts are recognized and commemorated and that we recognize the valuable contributions of Canadian Armed Forces Veterans who have served our country in domestic operations such as wildfires, ice storms and floods.”

Prime Minister’s Mandate Letter to the Minister of Veterans Affairs, 2021

Eligibility for the medal should also include any federal, provincial, or municipal personnel who take part in the coordinated response to a disaster which is declared a national emergency, whether the military is deployed or not. Time requirements should be minimal, ensuring that personnel deployed for short periods, such as first responders who are subsequently relieved or events such as plane crashes, which could only be days at most, are eligible.

Advocates have argued that the government should strike a new medal, such as a General Service Medal or strike a DOMESTIC bar for the Special Service Medal. However, if awarding a bar to the Special Service Medal, there is no possibility for the awarding of multiple deployments; some members of the CAF have deployed on numerous domestic operations, accumulating a hundred or more days, especially in the western provinces, where forest fires are a frequent issue. A standalone medal would allow bars or other ribbon devices to denote subsequent deployments.

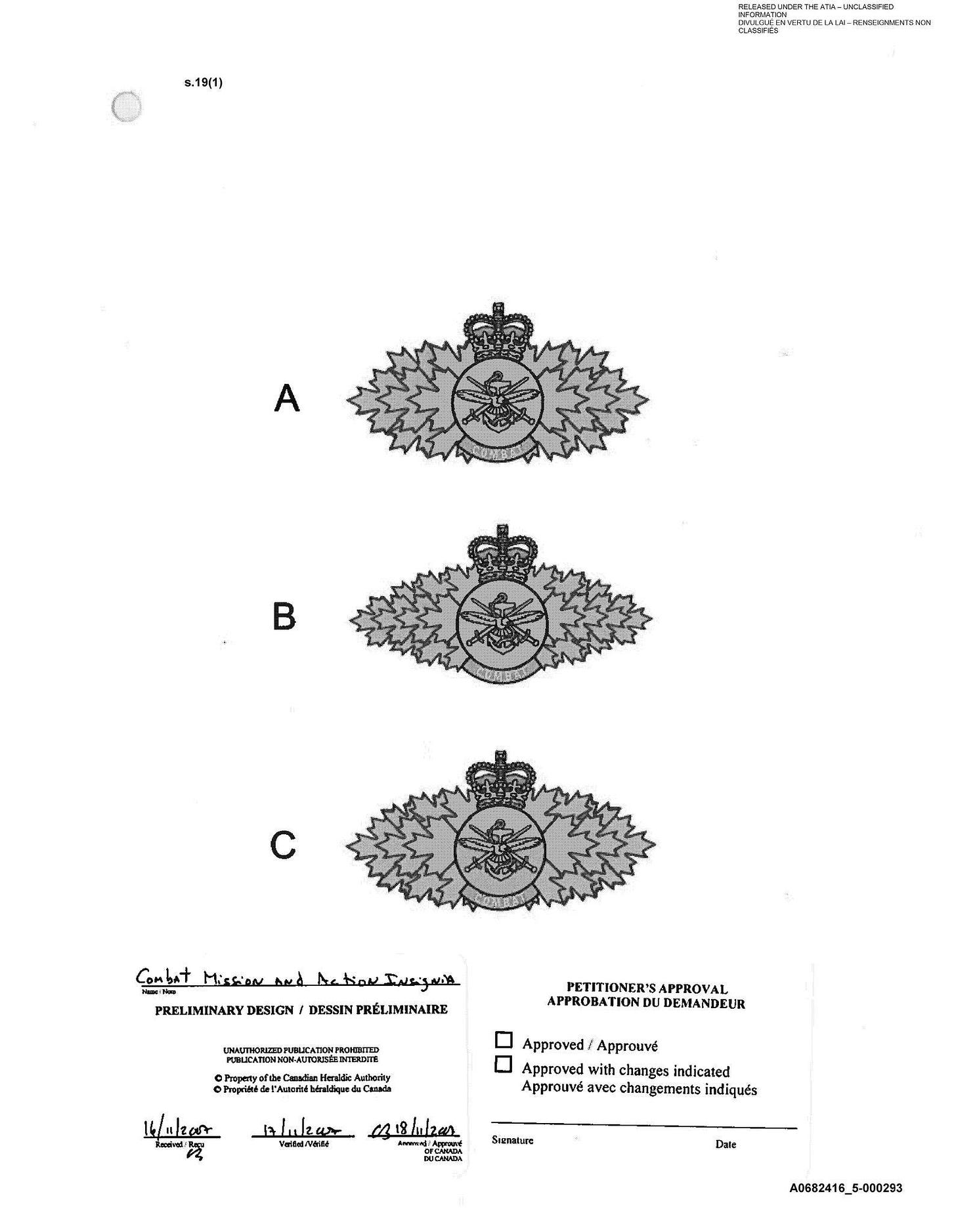

COMBAT ACTION BADGE

The proposed Combat Action Badge would recognize CAF members and officers who performed honourably in combat against an armed enemy. The badge was intended to be awarded in three categories, bronze, silver, and gold, to denote the large spectrum of combat operations.

Campaigns for the creation of the honour have been ongoing for decades now. For many of the soldiers who served in Afghanistan, especially those who went “outside the wire” and fought insurgents, there was a feeling of worthlessness for having received the same recognition, no more, than those who served in the offices in relative safety. Some even renounced the General Campaign Star they received. Veterans point to the US Combat Infantryman Badge and Combat Action Badge and the Australian Infantry Combat Badge and Army Combat Badge as proof that it is possible to administer. Advocacy campaigns have been launched to engage members of parliament and DND. Combat veterans are irate at NDHQ and DHH for their comments on why the award was cancelled.

“Never has Canada ever so under valued and poorly awarded any generation of soldier in any conflict of war than that of the Afghanistan Veteran. Afghanistan being the longest war in Canadian history. 158 CF members would be killed in Afghanistan over the 14 years that our country was deployed there.”

Sgt (ret’d) Ryan Gingras,

Afghanistan Combat Veteran, Founder of the “Mission Recognition” Facebook group

Documents from DHH, obtained and shared by Gingras through Access to Information (ATIP) and reported in the Ottawa Citizen, show that there was indeed work done to develop a badge with clear direction from the CDS; however, it was ended when DHH failed to arrive at a consensus on the criteria. Despite the CAF leadership’s endorsement and a clear desire for recognition from Afghanistan combat veterans, DHH recommended the termination of the project. Officially, DHH claimed the award would create two tiers of Honours, stating that the award would favour army combat arms trades over the rest of the CAF and that soldiers would be tempted to violate the rules of engagement (ROE) to qualify.

Documents from the ATIP show that DHH failed to reach a consensus on the eligibility and design. The ATIP, however, shows that a design was approved. DHH also failed to adhere to the definition of combat in the Honours Policy when attempting to determine eligibility; purposefully, advocates allege. It may be controversial to some, however, IED strikes, mine strikes, rocket strikes, mortar strikes, or artillery strikes are not combat. Combat is when two armed opposing forces are fighting with the intent to kill the opposition, colloquially in “contact” with the enemy.

“War, armed conflict or combat operations in the presence of an armed enemy. This includes situations short of war if the troops are in “combat” with an organized, armed “enemy” that is recognized as such by the Canadian people. It must be understood however that “combat” is not merely the presence of fire; rather, the fire has to be directed at our troops, with the intent of our troops being the destruction of the opposing force as a valid entity. The word “enemy” in this context means a hostile armed force, and includes armed terrorists, armed mutineers, armed rebels, armed rioters and armed pirates.”

Definition of War, Figure 2-1A, Canadian Forces Honours Policy

DHH alleged that they don’t want a system with two tiers of awards, yet there already is: the one which benefits them. As shown in the Toxic Military Leadership section, the system disproportionally benefits senior officers, especially those on track for top-level leadership, with access to foreign merit decorations, Meritorious Service Decorations, and appointments to the Order of Military Merit. Many proposed honours and awards would benefit the rank and file, not leadership at NDHQ; the Combat Action Badge is just one example.

The argument that the award would disproportionally benefit the Army is technically true, but it is a farce. There are many awards in the CAF that disproportionally benefit the Navy and Air Force, such as the Sea Service Badge (recognizing days at sea), the Naval Warfare Officer Badge (recognizing an officer’s progress towards command of a ship), or the sheer number of aircrew badges for the Air Force. There has been no pushback from combat veterans against awarding any badges that disproportionally benefit others. If DHH is unable to administer a Combat Action Badge that serves all elements and all trades, Canada could take a more literal cue from our allies in Australia and the US and create Army-only awards for Combat Infantry and Combat Action. The Air Force and Navy may choose to create their own.

DHH’s more egregious assertion is that soldiers would violate the ROEs to qualify for the award. Advocates allege this accusation demonstrates just how toxic and out-of-touch leadership at NDHQ truly is. The violation of the ROEs, as DHH asserts, would at the least endanger lives and, at worst, constitute a war crime, not to mention a complete violation of the training, professionalism, and ethos of the military. The assertion would require beneficiaries to commit fraud. And not just a single actor; their assertion would require a conspiracy among multiple levels of Battle Group leadership, officers, and NCOs. This assertion demonstrates just how little the out-of-touch toxic leadership understands what service is like for front-line soldiers, which advocates argue expressly demonstrates the need for the Combat Action Badge.

This assertion, insulting as it is, has no evidence to support it. There is no evidence of Canadian soldiers defrauding the military to receive awards in combat. It would be extremely challenging for junior soldiers and officers to accomplish given that this fraud would require corroborating contact reports, battle damage assessments, patrol reports, mission orders, communication journals, communication recordings, and command concurrence. Rumours circulated of officers in Afghanistan trying to get outside the wire to get qualified for the Combat Action Badge, but staff officers supposedly perpetrated these at Kandahar Airfield and few in number. The assertion also fails to mention the strict enforcement of administrative discipline and military justice; any attempt to defraud the military for any reason, not to mention a violation of the ROEs or reckless endangerment, would be severely punished.

The award recognizes that the bearer did what most, even amongst CAF members, did not, which makes their service rare and noteworthy. Only those who have fought an armed enemy, only those who have been hunted by a competent enemy, and only those who have had to fight not just for their own survival but for mission success can understand what makes combat different from other forms of service. But it is different. Only in combat are the stakes as high, when failure is not just personal or professional but strategic and diplomatic, and when death is not accidental but intentional.

CANADIAN VOLUNTEER SERVICE MEDAL / CANADA DEFENCE MEDAL

The proposed medal would recognize Canadians who have volunteered to serve in the CAF and completed basic training.

The Canadian Volunteer Service Medal is a historical medal awarded to those who volunteered to serve during periods of war, such as during the Second World War and Korea. It was meant to distinguish between those who volunteered and those who were drafted. Veterans of the Korean War fought until 1991, before the government recognized that Canadians had volunteered to serve again when their country asked and presented the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal for Korea.

Modern advocates call for the medal, or a version of it, to be struck and issued again. Advocates argue that the Canadian Forces Decoration is insufficient in recognizing military service, as those who spend less than 12 years and are unable to deploy would go unrecognized despite their service to their country. The medal would also benefit those who volunteered to serve but were injured in training and unable to serve a full career. Advocates are further arguing that the medal could benefit the CAFs' recruiting and retention efforts.

There are grassroots efforts to strike the medal, including two paper petitions to Parliament, 432-01203 and 432-00952, and three e-petitions, e-127, e-1418, and e-3224.

Additionally, there is a newer proposition that would serve the same goals: the Canada Defence Medal. Advocacy for the medal makes clear that it would recognize those who volunteer to serve in the Canadian Armed Forces and would be a successor to the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal.

The potential of this award goes beyond recognition, recruiting, and retention; it could also combat stolen valor. If the Chancellery of Honours at the Governor General's Office tracked this medal and made it available on the searchable database, it could serve as proof of service and easily disprove false claims of military service.

KUWAIT LIBERATION MEDAL

The Kuwait Liberation Medal is a five-class medal awarded to Kuwaiti and foreign militaries who participated in the Liberation of Kuwait.

The Medal was created in 1994 by the States of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia and offered to all participants of the Gulf War from 2 August 1990 through 31 August 1993. Kuwait’s Ambassador to Canada presented many of these medals to Canadian veterans of the Gulf War; the Canadian Government decried that Canadians may accept the medal, but it could not be worn with their Canadian medals.

The medal is awarded in five classes, separated by rank. The fifth class is for non-commissioned members, the fourth for warrant officers and junior officers, the third for senior officers, the second for one- or two-star generals, and the first class was reserved for three- or four-star generals. Despite the policy on dual recognition for service medals, the Canadian government authorized four Canadians to wear this medal, recipients of the first and second class of the medal. While Canada, Australia and the UK did not authorize the wearing of the medals, except for the four Canadians who received the first and second class, France, Italy, and the US allowed their military members and veterans to wear this medal. In a fine display of senior leadership putting the troops first, the US only accepted the fifth medal class.

Canadian Gulf War Veterans, including RAdm (ret’d) Summers, who commanded Canada’s Gulf War contingent and was a recipient of the first class of the Kuwait Liberation Medal, are demanding the government direct DND and the GG to allow recipients of all classes, not just the most senior officers, to wear this medal with their Canadian medals. The policy and argument against dual recognition are flawed, not just for the evident elitism that NDHQ persists in allowing only two admirals and a lieutenant colonel to wear the medal, but in other examples of dual recognition of service medals.

“… I am not allowed to wear this medal on this side, over my heart, and every time the ambassador of Kuwait sees it, it's embarrassing for us both.”

WO (ret’d) Kevin Samson,

Gulf War Veteran and President of the Rwanda Veterans Association of Canada

“It's a country that we helped liberate, and we can't do anything. We have been told no.”

MCpl (ret’d) Harold Davis,

Gulf War Veteran and President of the Persian Gulf Veterans Association of Canada

Advocates argue that the Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal is awarded for service on a peacekeeping operation with either the United Nations or NATO; the medal is awarded with the service medal for that particular operation. Also, many soldiers who deployed to Afghanistan were awarded the General Campaign Star along with the South-West Asia Service Medal for one deployment, and further still, some who were deployed to Camp Mirage, a support base outside Afghanistan, and flew in and out of Kandahar were awarded the General Service Medal and General Campaign Star. These types of deployments are common enough for CAF members to colloquially refer to these types of deployments as two-medal tours.

NDHQ made clear in testimony to Parliament that the medal goes against the policy for dual recognition. The policy is clear that dual recognition is not possible for service medals. However, the policy is also clear about awarding the Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal and a mission-specific service medal. It is also clear that dual recognition is possible if a member moves between operations areas and accumulates the required time for both theatres. The policy also states that foreign awards of merit may be awarded in addition to the campaign or service medal, which may describe the Kuwait Liberation Medal.

The Kuwait Liberation Medal is awarded not for mere service but for the Liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi Forces. It’s awarded in five classes, akin to other merit awards and orders of merit. The policy for foreign awards states that foreign awards of merit can be awarded as they focus on the donor country’s benefit. This interpretation was applied to recipients of the first and second classes of the award, but not to the classes that the junior officers and non-commissioned members received.

CROSS FOR THE FOUR-DAY MARCHES

The Cross of the Four-Day Marches is awarded for completing the annual International Four-Day Marches in Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

The Four Days March, also known as the March of the World, is a four-day 40km walking competition which began in 1909. In 1916, its military roots took hold as Dutch Soldiers on standby for World War One took part in the Marches to alleviate boredom and foster endurance. International militaries continued participating in the tradition throughout the Second World War and beyond. Thousands have completed the Four Days March, and hundreds of Canadians have been unable to wear their decoration. It has become a tradition for Canadian military units to undertake the challenge when they celebrate anniversaries. Hundreds of CAF members and veterans have been awarded the Cross of the Four Days Marches.

The Cross of the Four Day Marches, “Kruis Voor Betoonde Marsvaardigheid” in Dutch, also known as “Vierdaagsekruis” or colloquially the Nijmegen Medal, is an official Dutch Decoration created in 1909 by Royal Decree and awarded to those who complete all four days. The Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, and the US permit their military members to wear the decoration with their official honours, while Canada, Ireland, Israel, and the UK do not.

REVIEW OF CANADIAN FORCES HONOURS POLICY

Policy is not written in stone; policies are supposed to evolve as society evolves. Many of the CAF’s policies have been rightfully challenged in recent years, leading to apologies, class action lawsuits, and progress. The Canadian Forces Honours Policy is designed to maintain the integrity of Honours from losing their value by forbidding frivolous creations, but none of this advocacy is frivolous; every potential Honour listed above is, at the least, deserving of discussion and consideration. Advocacy against the creation of these Honours centres on old notions of service without recognition for the sake of service itself and keeping our system from turning into the United States Military’s system, which is drastically more liberal than ours. However, we would have a long way to go before frivolous becomes an issue, as one common belief among serving members and veterans is that our system is far too conservative.

The Honours Policy does not reflect the modern CAF. For instance, Chapter 1 Para 15, Medals, states that mainly administrative service does not warrant special recognition, however, many foreign and meritorious decorations are awarded for precisely this. It also states that time at sea does not merit special recognition; while the Navy may not award a medal for sea time, they do, however, award a Departmental Award. This is not to suggest that the Sea Service Badge should be removed; it does suggest that the policy is outdated. This is also the piece which limits the ability of NDHQ to strike a Domestic Operations Medal; to best serve the members of the CAF, this paragraph should be struck.

“15. Conversely, exchange, diplomatic or liaison duties, or other foreign service mainly administrative in nature, national operations such as in the defence of Canada, aid to civil authorities, exercises, time at sea and other similar duties are considered part of the regular duties of members of the CF and as such do not warrant special recognition apart from the award of the CD.”

Chapter 1, Canadian Forces Honours Policy

Discussions for Honours creation are extremely top-heavy; the beneficiaries are not truly considered. The policy gathers together an Honours Policy Committee to advise the CDS and the Chancellery of Honours; however, these positions are filled by senior officers and senior NCOs within NDHQ. The above recommendations would not benefit most of those in positions of power at NDHQ. Documents show that DHH expressly ignored the demands of combat veterans who called for a Combat Action Badge while in Afghanistan after their input was requested. Field units and reserve units fill most positions on Domestic Operations. There is little to no voice for the true beneficiaries of proposed Honours in the creation process.

“23. One guiding principle for military honours is that proposals for new awards are always made in consultation with the CF. That is, the views of those who would actually qualify for and be honoured by each award are given great weight. A CFHPC representing the CF studies these matters in depth and is responsible to maintain the high standards established in the past.”

Chapter 1, Canadian Forces Honours Policy

SPECIAL PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE ON HONOURS

Special Committees of Parliament are parliamentary committees formed to study a specific issue of national importance. The last Special Committee to study Honours and Decorations was established in 1942, over 80 years ago.

While the government can address many demands for new honours with an Order-in-Council, which will be required anyway, and legislative amendments to address the shortcomings in the Stolen Valor legislation, much of the issues are with the system and its administrators. The Special Committee could also study the backlogs for award nominations and approvals at the Chancellery of Honours. The government is mandated to oversee Honours when the Prime Minister, who has Ministerial Responsibility, deems it so. The issues in the previous section need more than a band-aid solution; the system needs to be reformed and policies modernized.

CONCLUSION

The members and officers of the Canadian Armed Forces have volunteered to stand tall in combat, facing off against an armed enemy determined and able to kill them, to deploy to disaster zones and stand witness to the suffering of Canadians while labouring to mitigate the destruction, and taking an active role in world-changing events where the stakes are at their highest. All they are asking for is to be recognized for doing so. Meanwhile, Governments continue centuries-old traditions of fighting tooth and nail against progress, dragging their feet, and gatekeeping the benefits for themselves despite claiming to honour the legacy and courage of the CAF members they represent.

Canada would have a long way to go before honours lose value by undermining them with too many awards. In the name of conservation and an over-abundance of caution, the policy has failed to uphold its purpose: to recognize those who undertake the gravest of endeavours and make Canadians proud.

Wow.

This was quite the post.

A couple of points from a CAF perspective, as someone who both received and nominated people for a variety of honours.

Yes, you’re correct in saying that the system is politicized. In fact, I was *directed* to nominate someone for a high honour, for entirely political reasons. However, you neglect to account for a few things. First, the OMM isn’t designed to award performance. It’s our equivalent to a knighthood (such as it is) and is supposed to honour extended service to the nation as a whole. Does it do that adequately? That’s a point for discussion.

Foreign awards are, of course, made by foreign governments. It’s simply a fact that most Canadian military personnel working with foreign forces are fairly senior. There are far, far fewer opportunities for junior members to do so. I remember when the leadership of the 3 PPCLI Battle Group on Op APOLLO was awarded Bronze Stars (without V device) by the US. The whining was something to behold from troops that assumed that the Canadians had *asked* for the medal and that it was some sort of valour award. Suck it up.

The MSC/MSM are now far, far easier to obtain than, say, twenty years ago. The same holds true for CDS Commendations and the like. Awards are now being given for activities that certainly would have been denied just a few years ago. This is where you need to look, not the OMM.

The Combat Action Badge. I’m a Combat Veteran(™) and hated this idea when it was first floated and hate it now. Why? First, isn’t a Canadian tradition at all and borrows heavily from the US. It seems that we *have* to have an equivalent to everything American.

Secondly, it further encourages an “us vs them” mentality. We already see far too many veterans distinguishing between *types* of service, feeling that their service is somehow more valuable and more worthy than other veterans. It isn’t and a Combat Action Badge would dramatically exacerbate this situation. Who’s to say that a RCEME tech performing field repairs on a dangerous MSR, virtually unprotected and in grave danger is less of a combat vet than an infantry soldier in the stack. Hell no.

As for the rest of the ideas for gongs, whatever. I actually think more medals, especially if they’re made retroactive, would create a nightmare as all the gong hunters that don’t have a deployment suddenly scramble to “prove” that their domestic service qualifies. If the criterion weren’t *tight* and extremely specific, you risk creating a free for all. For my part. I don’t care. Adding a couple of new medals only means paying to get them mounted yet again.

In regards to STOLEN VALOUR.

We remember the blood, sweat and tears that it took to earn a piece of metal attached to coloured ribbon, a strip of cloth or an embroidered badge, and that is why we get somewhat emotional about them.

Over the course of the past 11 years, it’s become apparent that the vast majority of individuals reported to us are nothing more than grifters & con artists who lie, cheat or steal for their own personal gain!

Fakery is not flattery, it’s cold, calculated deception with the goal of having one’s self-esteem issues assuaged by basking in the reflected glory of honourable men and women who have selflessly served this great country. We are often asked how do posers, fakes and embellishers gain from their medallic fuckery™?

They have used their “special status” to attend armed forces ceremonies and parades, military themed galas and high profile sporting events as VIP guests. Some have participated in fully funded overseas pilgrimages & adventurous expeditions, more have “advocated” on veterans issues without the requisite knowledge, experience or service!

Fakes and embellishers have even acquired “trauma support” dogs and mobility equipment that should have gone to legitimate veterans. Many have used their fake military narratives and tales of battlefield injuries to advance their employment opportunities & political aspirations.

Others are involved in intimidation, theft, fraud including accessing veteran/military discounts, questionable charity schemes, embezzlement and dating scams.

We are well aware of individuals using their fabricated experiences and bogus medals to justify and/or elicit sympathy for their bad behaviour, this is particularly evident with those who claim to have been Prisoners of War.

One absolute fake, claiming to be a combat wounded, Vietnam Vet had his “service” honoured by a professionally painted portrait by a volunteer artist!

We have found that Mental Health issues are not usually a factor in the cases reported to us. However, we have piquetted and bypassed a small number of individuals who clearly don’t have the intellectual/mental capacity to understand the nature of their actions.

In fact, we have channeled a number of individuals to mental health agencies as our interactions with them caused us some concerns.

As 18th-century British writer Samuel Johnson once said, “Every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier or not having been at sea.”